THE LAST LONGEST DAY

The Adventure of a Photographer: Wherein the photographer makes one good picture every minute from dawn to dusk on the longest day of the last year of the millennium. Shot on film. 4:27 AM to 23:10 PM June 21, 1999

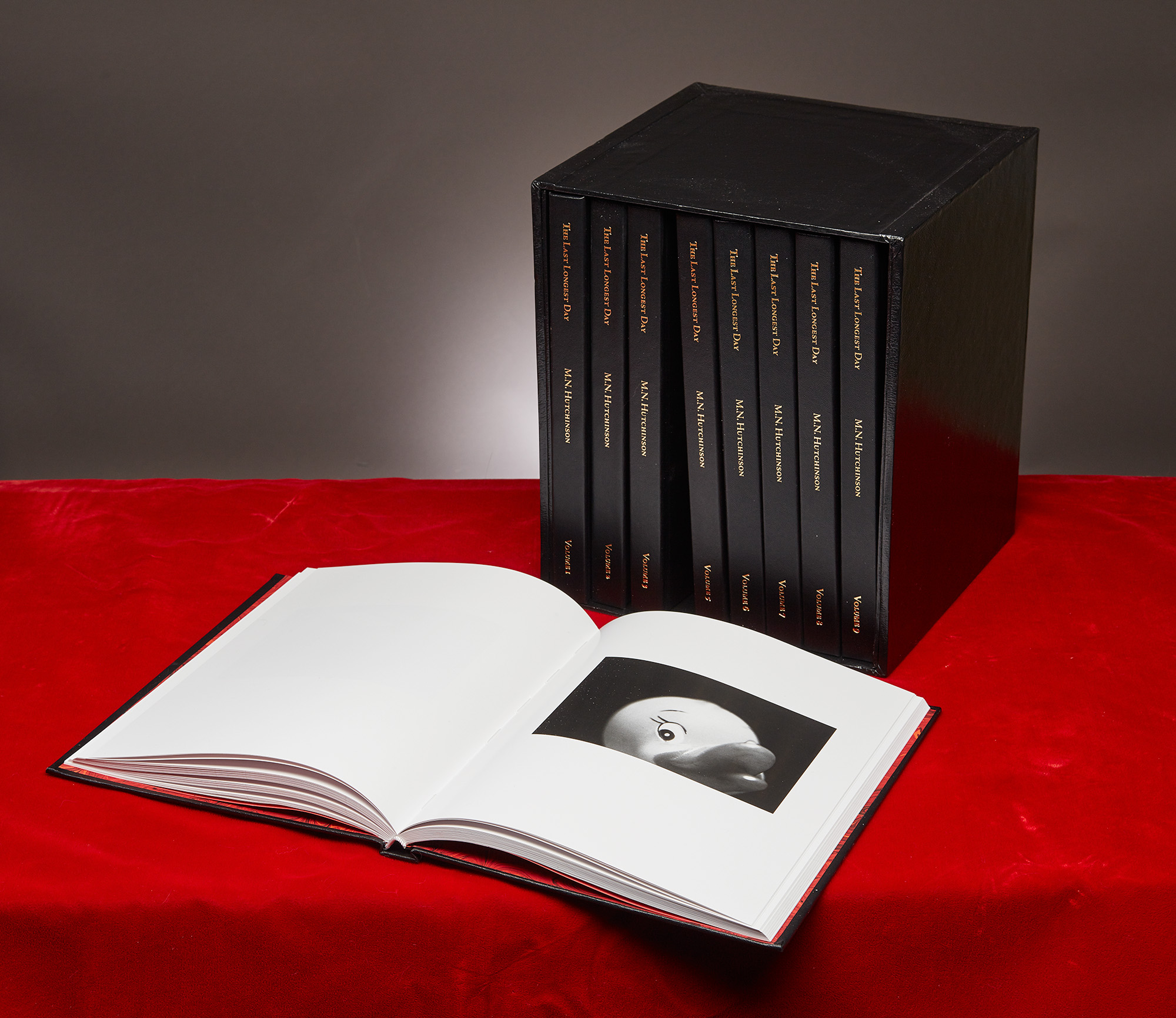

The Books

The Last Longest Day in book form.

9 Volumes, 100 pages each.

Hardcover, Endpapers, Slipcase

The Last Longest Day

by Nancy Tousley

On June 21, 1999, M.N. Hutchinson got up before daybreak and set out with an objective. He would take one photograph every minute of the day from sunrise at 04:23 to sunset at 23:10. He chose the date of the 1999 summer solstice because it was the last longest day of the year and of the millennium, and it was the day that offered the longest stretch of daylight in which to take pictures. Over the course of nearly 19 hours, he took 902 black-and-white photographs. He was doing more than just point-and-shoot. He was selecting the shot, composing it, adjusting the focus, checking the exposure, calculating the tonal range: all the things a photographer does to make a good picture. The mental concentration this took was demanding, but he was surprised by the physicality of the undertaking and amount of physical energy the project consumed. Everywhere he looked there was a potential photograph. By the end of the day he was exhausted. The event was a kind of endurance performance.

After 25 years as a photographer, Hutchinson’s goal at age 41 was “to prove that half a lifetime of taking photographs had made me see the world differently than someone who didn’t take pictures.” He developed contact sheets of the negatives he exposed, but then he put the project aside. He did not take the next step of going into the darkroom to make photographic prints, until now, 17 years later. To make that many prints by hand using wet darkroom processes seemed daunting. With the digital technology he started to use in 2005, it would have been a snap. In spite of that, to prepare the 106 prints chosen for the exhibition “M.N. Hutchinson: The Last Longest Day,” he took the film negatives not to the scanner and computer but back to the enlarger, the trays and the chemicals in the dim red light of the darkroom that he hadn’t used in years. He did this to maintain the integrity of his original intention and to follow it through using the analogue technology he started out with. The project, a conceptual artwork, would pose questions that were as much about the photographer as they were about photography itself. He sees the work now as a self-portrait, albeit an extended one, among the many others that marked his practice for 30 years and that he only recently ceased to make.

Hutchinson prepared for the July 21, 1999 shoot as though it were an expedition. Although he guessed at what he would need, he methodically assembled his gear for the day: two 35 mm Contax SLR cameras, 40 canisters of film that he rolled by hand from a 100’ strip, four camera lenses (25 mm, 60 mm, 85 mm and 180 mm), two pounds of batteries, a digital egg timer, and other bits of equipment. The latter included sweaters and hats; even on the longest day of the year, the morning air at 04:00 was chilly. His camera bag weighed 25 pounds. One of the physical demands of the day was simply carrying it around. Another was continually holding the camera’s viewfinder to his eye. By 10:30 his back was beginning to hurt. He had been shooting for more than six hours. By sunset, he wondered how he had been able to stick it out all day. “Between 20:00 to 23:00 hours,” he says, “I have no memory of the day, only the reconstruction through photographs of what I did and where I went.”

The madness inherent in Hutchinson’s project is present in the literary source that inspired it. Italo Calvino’s philosophical short story, “The Adventure of a Photographer,” was written in 1955. In the story, from Calvino’s book Difficult Loves, a non-photographer is led to take up the camera. He begins by taking snapshots and gradually becomes so obsessed with photography that his passion for it consumes everything else. In the end, unable to interact with the world and enthralled by the photographic image, he photographs photographs and nothing else. Before this occurs, he expounds on a theory. Once you have begun taking photographs, he muses, “there is no reason why you should stop. The line between the reality that is photographed because it seems beautiful to us and the reality that seems beautiful because it has been photographed is very narrow. . . . For the person who wants to capture everything that passes before his eyes, . . . the only coherent way to act is to snap at least one picture a minute, from the instant he opens his eyes in the morning to when he goes to sleep. This is the only way that the rolls of exposed film will represent a faithful diary of our days, with nothing left out. If I were to start taking pictures, I’d see this thing through, even if it meant losing my mind.”

Given developments after 1970, when rephotography, or making photographs of photographs, became a strategy of both conceptual art and documentary photography, whether or not Calvino’s protagonist should be seen as going mad is moot. In any event, Hutchinson’s project had a different intention: It was not a “faithful diary of our days, with nothing left out.” Instead, it showed off the camera as a tool of selection for the framing and taking of autonomous single images. Still these were not “decisive moments” a la Cartier-Bresson, but the result of what Hutchinson calls “determined looking,” slices of a continuum collected in a manner more in tune with the strategies of street photography. Thus the totality was also not a narrative. In keeping with the idea that the project is a self-portrait, the places that the Calgary-based artist chose to photograph were inside and outside his house in Bowness, nearby Bowness Park, and sites he gravitated toward when, at age 12, he first started making photographs with a borrowed camera, his father’s Minolta Rangerfinder. They included downtown Calgary, Chinatown, and the Calgary Zoo. At the same time, starting with the premise that everything he saw had the potential to become a good photograph, he didn’t really care where he was. The photographs he took were the test results of his discipline, control, alertness, agility, visual acuity, and formal dexterity at mid life — and of his ability to make a good picture every 60 seconds.

What made any one of these pictures good? For Hutchinson, the criteria are mostly formal — “composition, point of view, exposure, focus or lack thereof, translation of the image into black-and-white, film development and printing” — with subject matter being a lesser concern. Part of the challenge of making them was the fact that the one-minute rule went against his training as a studio photographer and everything in his practice up to that point. “The core was that you created photographs by putting things together,” Hutchinson says. “That was my life.” It was a process that eliminated chance. It was based on ideas and images that he formulated in his head. His studio work in the summer of 1999 was making large colour lenticular photographs of small objects, like yellow rubber ducks and soothers, which were the antithesis of those he went out that day to find.

“This project was built around observation so it was a departure for me,” he says. “It’s a bit of a hybrid because you’re making something from what’s in front of you. You go looking for potential photographs. This was forcing the subject matter onto the film.” It went against the snapshot and eschewed spectacle. “Snapshots are mostly of people and places that are considered significant before you take the picture,” says Hutchinson. His photographs taken one every minute gave significance to their subjects by making them into images that he could relate to his experience and the history and traditions of photography. Part of his strategy, in some photographs, was to invoke the work of photographers he admired, like Eugene Atget, the great French photographer of Paris in the early 20th century, and the Americans Lee Friedlander, Lewis Baltz, Gary Winogrand, Harry Callahan, and Imogen Cunningham. “While I didn’t set out to emulate any single photographer,” he says, “the weight of observational photography was certainly on my mind. I was not trying to make anything new at all, but to work within a tradition of photography that would test my ability to respond in a typical fashion to the world around me.”

Photography’s unique capacity is to arrest time and the photographer’s job is to know when to click the shutter, as Janet Malcolm observed in Diana and Nikon (1980). Chance, however, also can play a significant role in the resolution of a photograph. Robin Kelsey’s Photography and the Art of Chance (2015) looks at this proposition in great detail. But as much it might seem to open the door, Hutchinson’s one-minute rule constrained chance and, to a greater degree, spontaneity. “Even if you saw a perfect picture happen in front of you, the one-picture-a-minute rule would make it impossible to be spontaneous,” he says. “A photographer has to ask continuously if it’s time yet to make a picture, both for those things that happen too fast and those that happen too slowly. There was a sense of determinism that replaced spontaneity.” Chance presented itself in the opportunities that appeared in front of him. Could he make a good photograph? Which ones would he miss because of the one-minute rule? How many shots would he take simply because of it?

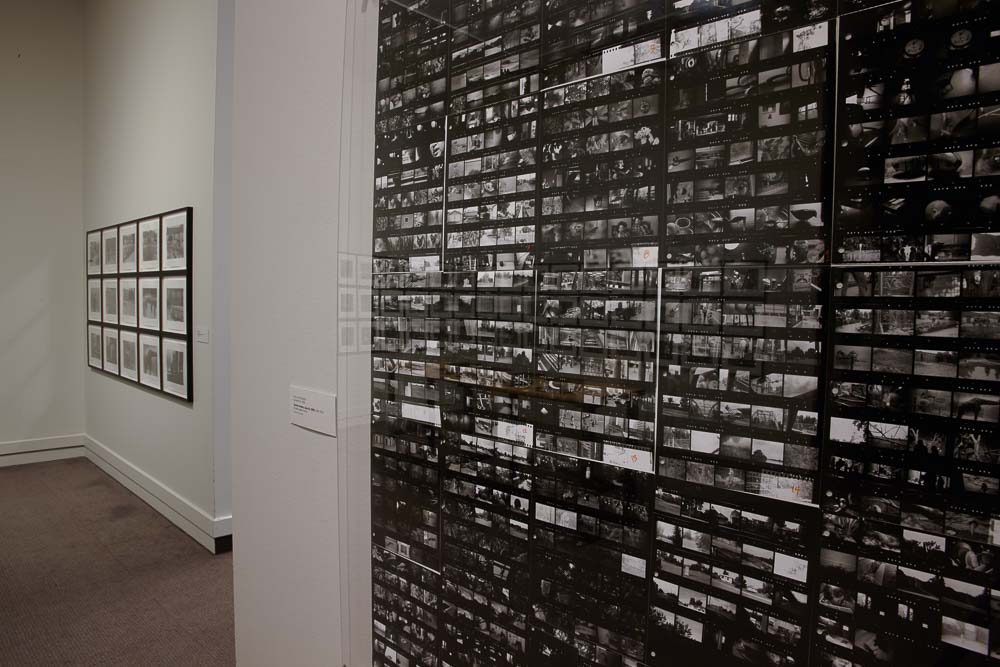

Relying on his experience and knowledge of the medium, Hutchinson worked that day with remarkable verve and consistency. The photographic sequences in the exhibition “The Last Longest Day” are presented as units of time, from one photograph (representing one minute) to a grid of 60 photographs (representing one hour). All of the groups are unedited consecutive shots. Although Calvino inspired the idea for the project, it became pressing when Hutchinson realized that he had begun to look at everything for its potential as a photograph and the perfect day, the last longest day of the year and of the millennium, arrived. Had 25 years of taking photographs changed his vision of the world? Yes, it was bound to. The project offered an additional proof. All photographs, however and wherever they are produced, are made not captured, as the standard way of talking about photography suggests. There is nothing natural or unmediated about them. Hutchinson constructed the photographs in “The Last Longest Day” in that narrow space between “the reality that is photographed because it seems beautiful to us and the reality that seems beautiful because it has been photographed.” Nonetheless, he says, “The potential for beauty doesn’t rely on anything special occurring in front of you. It’s something you make.”